Throughout history, wars, conflicts, and crises have uprooted millions of people, forcing them to seek safety beyond their borders. We often think of refugees as a modern issue, but displacement has been happening for centuries—just in different forms. From the Vietnamese “boat people” in the 1970s to the Rohingya persecutions in 2017, the movement of refugees has shaped the modern world.

Malaysia, a country strategically located in Southeast Asia, has found itself at the crossroads of these global movements. While it has never been a primary refugee-producing nation, it has been a landing place for waves of people escaping violence and uncertainty. Over the decades, Malaysia has received refugees from Vietnam, Cambodia, Myanmar, Aceh, and even the Middle East, yet its stance on handling them has remained complex. Unlike some countries that have formal asylum systems, Malaysia operates in a legal gray area, offering temporary shelter but stopping short of granting official refugee status. Why? To answer that, we need to look at history.

A Brief History Of Refugees

In the aftermath of World War II, as Europe grappled with millions of displaced people, a global conversation about refugee rights emerged. This led to the 1951 Refugee Convention, a landmark agreement that laid out how refugees should be treated. Malaysia, however, never signed it. At the time, Malaysia was still under British colonial rule and had its own struggles—namely, preparing for independence and managing internal conflicts like the Communist insurgency. The plight of global refugees was not a priority.

Despite this, Malaysia soon became a temporary home for refugees. In the 1970s and 1980s, the country played a key role in hosting Vietnamese refugees, who arrived by the thousands on overcrowded boats after the fall of Saigon. Many were placed in camps before being resettled in Western countries like the US, Canada, and Australia. During this same period, Cambodian and Laotian refugees escaping war in Indochina also found temporary refuge in Malaysia.

Then came the Rohingya crisis, which would define Malaysia’s refugee landscape for decades. Starting in the 1980s but intensifying in the 2010s, waves of Rohingya Muslims fled Myanmar’s military persecution, making dangerous sea journeys to Malaysia. Unlike the Vietnamese, the Rohingya had no “next country” willing to take them in. They were not seen as temporary asylum seekers but as a long-term humanitarian challenge—one that Malaysia had no formal system to handle.

The Legal Limbo

Malaysia’s refusal to sign the 1951 Refugee Convention means that, legally, it does not recognize the difference between a refugee and an undocumented migrant. This creates a paradox: refugees are allowed to stay on humanitarian grounds but have no official rights. They cannot legally work, send their children to government schools, or access public healthcare without paying high fees. Every day, they risk arrest, detention, and deportation.

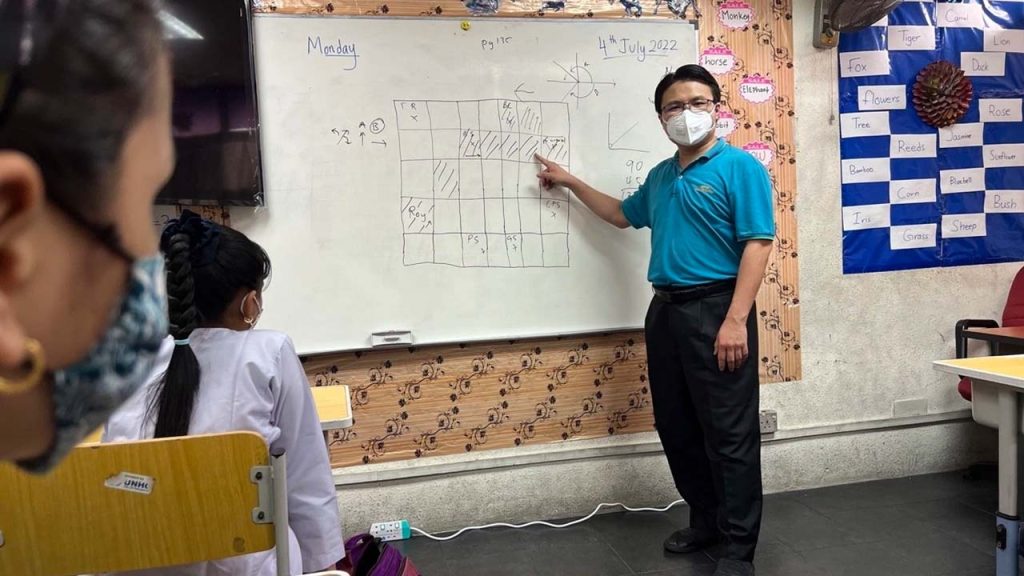

Yet, Malaysia does not turn them away completely. Instead, it relies on UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees) and local NGOs to fill the gaps. UNHCR registers refugees and issues ID cards, which offer some protection, but this is far from a real legal status. NGOs provide education, healthcare, and job training, but their resources are limited. The result? A refugee community that exists in the shadows—not officially welcomed, but not entirely rejected either.

The public perception of refugees is equally mixed. Some Malaysians sympathize with them, especially given the country’s Muslim identity and shared cultural ties with groups like the Rohingya. Others, however, see them as a burden on an already stretched economy, leading to political debates on whether Malaysia should continue accepting them. The government’s stance has remained consistent: Malaysia is willing to help, but not willing to commit legally.

Challenges And Opportunities Ahead

With nearly 200,000 refugees and asylum seekers now in Malaysia, the question remains—what next? The current system is unsustainable. Refugees need the ability to work and support themselves rather than relying on charity. At the same time, the government fears that granting them legal status would encourage more arrivals, leading to greater economic and social strain.

One possible solution is a structured work program, where refugees can legally contribute to industries facing labor shortages, like construction and agriculture. Some pilot programs have been tested, but none have been fully implemented. Another approach is regional cooperation—Malaysia could work with neighboring ASEAN countries to share responsibility for refugee resettlement rather than bearing the burden alone.

The truth is, refugees will continue to arrive, whether Malaysia is ready or not. Wars, political oppression, and economic collapse in nearby regions make displacement inevitable. The challenge for Malaysia is no longer whether to accept refugees—it already does—but how to integrate them in a way that benefits both refugees and the country.

Malaysia’s relationship with refugees is one of contradictions—humanitarian but hesitant, generous but cautious. And as history has shown, this relationship is far from over.

Meanwhile, organisations like Hati Nusantara is created to bridge support to the underserved refugee communities in Malaysia.